- Home

- Jen Beagin

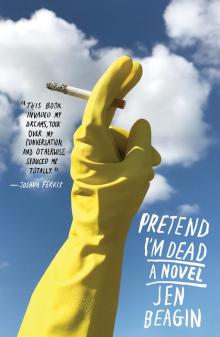

Pretend I'm Dead

Pretend I'm Dead Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Heffo

CONTENTS

Hole

Yoko and Yoko

Henry and Zoe

Betty

Acknowledgments

About the Author

HOLE

FOR MONTHS HE WAS JUST a number to her: she counted his dirties, he dropped them in the bucket, she recorded the number on the clipboard, and he moved down the line. Another pelican mired in oil, worn to the stump and nodding to his own ruin. A goner like the rest of them.

Then, after switching to the needle station—instead of counting, she handed out clean rigs—she noticed that he was the only exchanger carrying library books. Biographies, mostly, and crime fiction. She dubbed him Mr. Disgusting on account of his looks and dirty clothes. His hair was a long angry scribble in need of hot oil treatment, his face an overworked drawing with too many wrinkles, but he was tall and broad shouldered and could carry her around the block or up a flight of stairs if he ever needed or wanted to, a quality she’d found lacking in her previous boyfriends, and she was pretty much in love with his eyes, which were dark, frank in their expression, and seemed to say, You Are Here.

It was supposed to rain that night, the night of their first conversation. Half of the exchangers stood under a tarp; half were exposed to the stiff gray sky. The exposed ones looked sodden and miserable, even though it wasn’t raining yet. Mr. Disgusting stood toward the end of the line. Unlike the others, he looked perfectly at ease, a book shielding his face. She squinted at the title: Straight Life, the Story of Art Pepper—whoever that was. She was already anticipating the somatic effect his presence had on her: when he was within five feet she’d suddenly lose her peripheral vision along with all the saliva in her mouth, and her heart would beat as if being hunted. Seeing him was the highlight of her two-hour commitment and tonight she’d made adjustments to her wardrobe, ditching her high-tops and hooded sweatshirt for ballet flats and a vintage leopard-print cape. She was even wearing blush and a padded bra.

The line shuffled forward and soon he stood before her, smiling faintly. He was wearing the leather jacket she liked—once white, now scuffed and weatherworn, with a cryptic tire mark running directly up the back. There was a dead leaf in his hair she didn’t have the nerve to pluck out. She decided to stick to the script.

“How many?” she asked.

She expected the usual four clipped syllables: “Twenty-two, please.” Instead he replied, “I was fleeced last week.” He smiled with one side of his mouth. “Flimflammed,” he said.

It was her turn to say something, but she was too startled by his voice, which was distinct enough to be its own creature. It had a spine and sharp little teeth.

“Actually, the cops took them,” he said. “I just like saying flimflam.”

She smiled. “Where?”

“Couple blocks from here.”

The needle exchange was nothing more than supplies set up on roll-away carts, situated at the end of a little-known alley wedged between an abandoned convent and a Laotian bakery in what was called The Acre, a largely Cambodian neighborhood in Lowell. They’d been here five months but now it was October and soon they’d have to move indoors, somewhere under the radar.

“Must have been a rookie,” she said.

Their tacit understanding with the cops was that they could operate the exchange in peace, so long as the exchangers didn’t do anything stupid, such as sell needles for money or dope, or shoot up on the sidewalk, but occasionally the wrong cop wandered by and busted some hapless exchanger for possession and paraphernalia.

She shook out a paper bag and dropped in a starter kit. Technically, it was a one-for-one exchange, but if someone showed up empty-handed she gave them a bag of ten points and a small bottle of bleach.

“Thanks,” he said. “I appreciate it. But I don’t need the bleach.”

No bleach meant he didn’t clean his needles, which meant he probably didn’t share them. She took this to mean he was single and unattached. She handed him the bag with what she hoped was an easygoing smile. In fact she felt queasy. It was always over too soon, and now she’d have to wait another week. He mumbled thank you and she watched him walk down the alley. He never looked back at her.

* * *

HE BECAME A FURTIVE PRESENCE in her life. She fantasized about him every other day, usually while vacuuming. She made her living as a cleaning lady and daydreaming was a vital part of her happiness on the job. Knowing nothing but his taste in drugs and library books, the daydreams were loose and freewheeling. She gave him a Spanish accent, a pilot’s license, a way with words. She dressed him in various costumes—UPS uniform, lab coat, motorcycle leathers—and invented interesting monologues for him.

They had their second conversation three weeks later. The site had moved into the dingy waiting room of a free clinic two blocks south. She was working the supply table, handing out cotton balls, bleach, alcohol swabs, condoms, and donuts donated from the Lao bakery around the corner, perhaps in gratitude for moving out of their alleyway. The fluorescent lighting made her feel like she was in high school again, back when the medication had made her skin green and her nickname was Witchy. He asked for cotton and alcohol swabs. In an effort to prolong their encounter, she offered a handful of condoms—black, their most popular color—even though she suspected he didn’t need or want any, as he wasn’t a sex worker and his libido was likely a distant memory. He let out a sad laugh.

“What’s funny?” she asked, playing dumb.

“Oh, nothing,” he said, and shook his head. “It’s just that I have little use for condoms except as water balloons, which I also have little use for.”

He looked at the floor, seemingly searching for words. She grasped for something to fill the growing silence, but she was too captivated by his voice.

“Sorry,” he said. “I’ve made you uncomfortable with my creepy honesty.” He shook his head again.

“Not at all,” she said. “I’m actually a fan of creepy honesty.”

He made tentative eye contact. His eyes made her feel all gooey and exceptional, but the tension in his jaw told her he hadn’t fixed that day, and she wondered how far from the site he lived. Was he able to wait until he got home, or was he like some of the other exchangers, who spiked themselves in public?

“Would you care for a bear claw?” she asked.

He nodded.

“Take two,” she said, breaking the one-per-person rule.

He gave her a wide smile and she took a quick inventory of his teeth: all there, reasonably white, and sturdy enough to tear linoleum. A minor miracle.

“You’re very kind,” he said in an oddly deliberate way, as though speaking in code. She watched him turn abruptly, cross the street, and disappear around a corner.

* * *

HE VANISHED FOR MOST OF the winter. She figured he was either in rehab, prison, or the ground. In his absence she grew listless and bored and almost quit, but what the hell else was she going to do on Tuesday nights? She lived alone, sans television. Her only friend was attending college in another state. She had more in common with the exchangers than anyone she knew. They were both invisible to the rest of society—they by their status as junkies, she by her status as maid—and they’d both eat pretty much anythi

ng covered in frosting. Spending time with her fellow volunteers was just as edifying. No do-gooders, no show-offs, no save-the-children types. They chain-smoked and ate nachos and hot dogs from 7-Eleven—she admired that.

Mr. Disgusting reappeared one afternoon in early spring, looking like an out-of-work character actor. He wore a seven-day beard, old sunglasses with amber lenses, a long-sleeved, forest-green button-up, some extra weight around his middle. He shuffled up and asked to speak to her alone. Excusing herself, she walked to the corner, stopping before a boarded-up tanning salon called Darque Tan II. She was going to say “It’s good to see you,” then opted for something more neutral. “I haven’t seen you in a while.”

“Rehab.”

“I was hoping that’s where you were.”

“So you thought about me, then,” he said, removing his glasses.

“Are you okay?”

He put his sunglasses back on. “I’m not very good at this.”

“Good at what?”

He did some aggressive throat clearing. “I came here to give you something.” He handed her a shard of broken mirror the size of her palm. It was thick and sail shaped and worn smooth around the edges. She looked at it briefly and mumbled thank you.

“Turn it over,” he said impatiently.

He’d scrawled his name and phone number on the back in bright-pink crayon.

“I thought I’d put my number on a mirror so you can check yourself out while we’re talking on the phone.” He smiled.

She could tell he’d practiced the delivery of that line and she meant to reassure him, but was thrown off by the advice written on the wall behind him: “If God gives you lemons, find a new God.”

“That is, if you feel like talking,” he said.

She nodded slowly. In fact, she suddenly wasn’t sure about any of it—him, herself, herself with him. In her fantasies they never bothered with phone numbers. He just showed up, wordlessly threw her over his shoulder, and then he carried her down a different alley, where they did some violent making out against a brick wall.

“Do you even know my name?” she asked.

He blushed. “I’m convinced it starts with K,” he said.

“M,” she said. “It starts with M.”

“Mommy?”

She laughed. “Mona.”

“Hm,” he said. “Can I call you Mommy instead?”

“Maybe.” Turning away, she nodded toward the mouth of the alley, where one of her fellow volunteers was talking on a cell phone and openly staring at them. “Look, Big Brother’s watching.”

“You care what they think,” he said. “That’s why you won’t look at me?”

“I’m looking at you,” she said, then looked at the ground.

“Well, call me if you feel like it.”

She watched him walk away and thought back to the weekend of volunteer training mandated by the organization that ran the needle exchange. She and the other volunteers had role-played various hypothetical situations, such as what to do in the event that an exchanger inadvertently, or perhaps purposely, stuck you with a dirty needle. They never went over what to do if the exchanger handed you a broken mirror and asked you to call him sometime.

* * *

MOST DAYS SHE WORKED ALONE, in the fancy part of town, where many of the houses still had servants’ quarters left over from the last century. Her contact with the homeowners was limited, but when they discovered that English wasn’t her second language, they treated her warily, as if she were mentally ill, learning disabled, or an ex-con. They assumed she was sullied somehow. Disgraced. The fact that she was white, managed to graduate from a decent parochial high school, and yet chose to clean houses seemed beyond their comprehension.

Right now she was cleaning the Stones’ place with Sheila, her employer and legal guardian. The Stones lived in a sprawling Tudor mansion with a fireplace in every room, including the kitchen, which they were cleaning now. Sheila stood at the sink, rinsing dishes, and Mona was on her knees with her head in the oven, removing grease loosened with half a bottle of Easy-Off. Consequently, her skin was tingling and imaginary bionic noises accompanied the movement of her arms. Usually she enjoyed a good oven cleaner buzz, but just then she wanted to pull a Sylvia Plath. Sheila must have intuited as much, because she suddenly shut off the kitchen faucet and asked Mona if she was still taking her meds.

“Nope,” she said. “Been drug free for three weeks now.”

“How’s Dr. Tattleman?”

“I quit her, too.”

To Mona’s surprise, Sheila seemed unconcerned. Nonchalant, even. “Well, how’re you feeling?” she asked.

“Not as, uh, neutral as I’d like, but okay.”

“You don’t need to be any more neutral, honey,” she said, and sniffed.

Mona waited for the inevitable barrage of AA slogans. Sheila could string two hundred together in one sentence.

“I’m going to miss you,” Sheila said instead. “I miss you already.”

In four days Sheila was fucking off to Florida. For good. She’d sold her house and the business and had just closed on a condo in God’s waiting room, as she called it, where she planned to join a book club and take up golf.

“I wish you’d try group therapy,” Sheila said.

“I’m tired of talking.”

“Individual counseling promotes self-pity. There’s less wallowing in group, and you don’t have to talk if you don’t want to. You can share your pain and then just . . . turn it over, listen to someone else’s problems.”

“Turn it over?”

“To God,” she said. “You know, let go and let God?”

Let go and let God? Let go and let God. Let go, let God! Let go! Let God! Let go!

Lately phrases got stuck in her head and tumbled around for days. They made a terrible racket, like loose change in a dryer. Last week it was “Get bent, you stupid bitch,” which she’d heard someone shout from the open window of a pickup truck.

“You’re not even here,” Sheila said. “Where are you right now?”

“I’m here, I’m here.” It was only noon and already she was bone-tired. Sheila, on the other hand, was just getting warmed up—she made cleaning look like swing dancing. Right now she was loading a dozen cereal bowls into the dishwasher. Cereal was all Mr. Stone seemed to eat, and he left milky bowls in every room.

“The man has serious Mommy issues,” Mona said.

“Who?” Sheila said.

“Daddy Stone. The cereal bowls are like lactating boobs. He cradles them in his hand, shovels the cereal into his mouth, the milk dribbles down his chin, and it’s like he’s . . . nursing. He’s probably all pacified and drowsy afterward, which is why he can’t be bothered to bring the bowls to the kitchen.”

“Stop,” Sheila said. “He seems nice.”

“Did you see the bidet they installed in the master bath? They can’t even wipe their own asses.”

Sheila frowned. “I agree it was an interesting choice.”

Mona rolled her eyes. No matter how much Mona goaded her, Sheila refused to talk shit about their clients. “I’m sweating my balls off,” Mona said. “Will you scratch my back?”

Sheila dried her hands and leaned over to scratch Mona’s back.

“Higher,” she ordered.

“Maybe it’s time you got a dog.”

Mona laughed. “Why?”

“When you’re forced to do things that take you out of yourself—like picking up dog poop—that’s when you find yourself.”

“You hate your dog,” Mona reminded her. “He shits in your shoes, remember?”

“Go to the pound,” Sheila said. “Adopt another terrier.”

She’d grown up with two Jack Russells. This was back in Torrance, California. She’d named them Spoon and Fork. Spoon ran in circles, Fork in figure eights. They’d been loving and affectionate killing machines, and she’d loved them more than anyone, including her parents, but they’d been indomitable and were eventuall

y sent to a farm in Idaho, or so she was told, and then her parents got wild, too, and divorced each other and shacked up with new people, and a year later, when she was twelve, she was sent to live with Sheila, her father’s first cousin. Sheila was single, childless, and sober with a capital S, and she agreed to take Mona in without ever having met her. It was supposed to be just for a summer. She’d heard of Massachusetts, but for all she knew, New England was attached to England, or, if not attached, then possibly connected by a system of underground tunnels. Lowell and London, she imagined, were affiliated, and she envisioned herself walking along cobblestone streets in the fog, wearing a trench coat with the collar turned up, and living in a turret covered in ivy, images she’d culled from various movies and postcards.

“Service to others,” Sheila said now, snatching the dirty sponge from Mona’s hands and rinsing it in the sink. “It’ll take your focus off your own problems.” She squeezed water from the sponge and handed it back.

“Service to others,” Mona repeated.

“It leads to greatness, sweetie.”

“But I’m already a servant.”

“Doesn’t count,” she said. “You make money.”

“And I already volunteer, remember?”

“Yeah, but why’d you have to pick that? I mean, running abscesses? Barf.”

Mona shrugged and got to her feet. “What’s for lunch?”

“Leftover Chinese.”

Sheila nuked their lunch in the microwave. Crab rangoons, green beans, pork lo mein. They sat on stools in the butler’s pantry and looked out the arched window. The Stones’ garden was customarily pristine, but someone had maniacally hacked at all of their hydrangea bushes.

“Disgruntled gardener,” Mona said, pointing. “Or maybe Mrs. Stone lost her mind.”

Sheila nodded vaguely. “You know,” she said. “The summers are hotter than Haiti in Florida, so maybe I’ll spend part of August up here with you.”

“Hades,” Mona said.

“What?”

“Hades. Hotter than Hades.”

Pretend I'm Dead

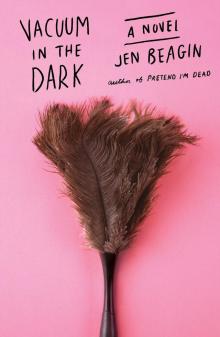

Pretend I'm Dead Vacuum in the Dark

Vacuum in the Dark